Download pdf: Potash for grass (1.79M)

pdf 1.79M

Potash for grass

June 2020

Potash for Grass

Potash regulates the movement and storage of solutes throughout the plant, comparable to the blood system in animals or humans. This is clearly a wide ranging and vital role, affecting nutrient uptake, photosynthesis, rate of growth and feed value of forage. These functions require larger amounts of total potash in the plant than any other nutrient including nitrogen. If adequate amounts are not present grass will not grow or yield as it should.

The practical implications of potash shortages are summarised in the following table:

| Deficient K | Satisfactory K |

| Lower yield | Full yield |

| Deterioration of sward composition | Maintenance of productive species |

| Less response to applied nitrogen | Maximum response to applied nitrogen |

| Increased risk of nitrogen loss | Minimal nitrogen loss |

| Less vigorous legume growth | Full potential legume contribution |

| Reduced nitrogen fixation by clover | Optimal nitrogen fixation by legumes |

| Risk of poor silage fermentation | Normal fermentation |

| Reduced protein production | Full protein production |

| Ranker, weak growth | Strong healthy growth |

| Greater susceptibility to frost | Less winter damage |

| Slower growth in spring | Earlier spring growth |

| Open swards, more sod pulling | Denser vigorous sward |

| Increased susceptibility to drought | Normal drought resistance |

| Increased disease susceptibility | Disease risk according to season |

| Poor recovery, especially in dry conditions | Quicker aftermath growth |

Potash supply

It is inefficient to allow soil reserves to fall to levels where grass growth is directly dependent upon fresh fertiliser applications.

The quantities of potash removed in silage are large and therefore clearly important to replace. It would be logical to return manures onto fields growing silage, hay or wholecrop cereals, but in practice, this may not occur. It’s common to find fields which regularly grow maize with high applications of manure that have excess soil P and K whilst grass silage fields do not receive manure and have deficient nutrient levels.

The situation is very different with grazing. Because around 90% of the potash in grazed grass is returned directly to the sward, the need for potash application is low. The return, however, may not be even and fertility can build up where animals congregate to drink, feed or lie, which means a run-down in other areas where they only graze. Common sense is needed when soil sampling to identify such differences, avoiding atypical areas.

Recommendations

The requirements for P and K to be supplied from fertilisers and organic manures are given below. The recommendations are calculated to achieve full yield and maintain, improve or reduce soil P and K according to the soil index.

Replacement values (M) are based on the average yields shown – if significantly different yields apply, the rates should be adjusted accordingly.

| kg/ha total over season | Soil Index | ||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2- | 2+ | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 | cut & graze (23 t/ha) | ||||||

| Phosphate | 100 | 70 | 40M | 20 | 4 | ||

| Potash | 200 | 170 | 140M | 120 | 30 | 0 | |

| Sulphur | 40 | ||||||

| 2 | cuts & graze (23+15 t/ha) | ||||||

| Phosphate | 125 | 95 | 65M | 20 | 0 | ||

| Potash | 320 | 270 | 230M | 180 | 70 | 0 | |

| Sulphur | 80 | ||||||

| 3 | cuts (23+15+9 t/ha) | ||||||

| Phosphate | 140 | 110 | 80M | 20 | 0 | ||

| Potash | 370 | 320 | 280M | 190 | 90 | 0 | |

| Sulphur | 120 | ||||||

| 4 | cuts (23+15+9+7 t/ha) | ||||||

| Phosphate | 150 | 120 | 90M | 20 | 0 | ||

| Potash | 410 | 390 | 350M | 230 | 110 | 0 | |

| Sulphur | 160 | ||||||

| 1 | cut hay & graze (5 t/ha) | ||||||

| Phosphate | 80 | 55 | 30M | 0 | 0 | ||

| Potash | 140 | 115 | 90M | 65 | 20 | 0 | |

| Sulphur | 40 | ||||||

| Grazed only | |||||||

| Phosphate | 80 | 50 | 20 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Potash | 60 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sulphur | 20-60 | ||||||

| Establishment (These rates should be deducted from first season’s requirements) | |||||||

| Phosphate | 120 | 80 | 50 | 30 | 0 | ||

| Potash | 120 | 80 | 60 | 40 | 0 | 0 | |

| PK fertiliser/manure plans are based on expected yields. If actual yields are very different, the over or under applied potash can be taken into consideration in the following year’s plan. | |||||||

Potash reductions at high indices

Where soils are above the target index of 2- for potash, fertiliser applications can be reduced or omitted as no response is likely and there is no benefit to having such high soil levels. In some situations, caution would be advised, however.

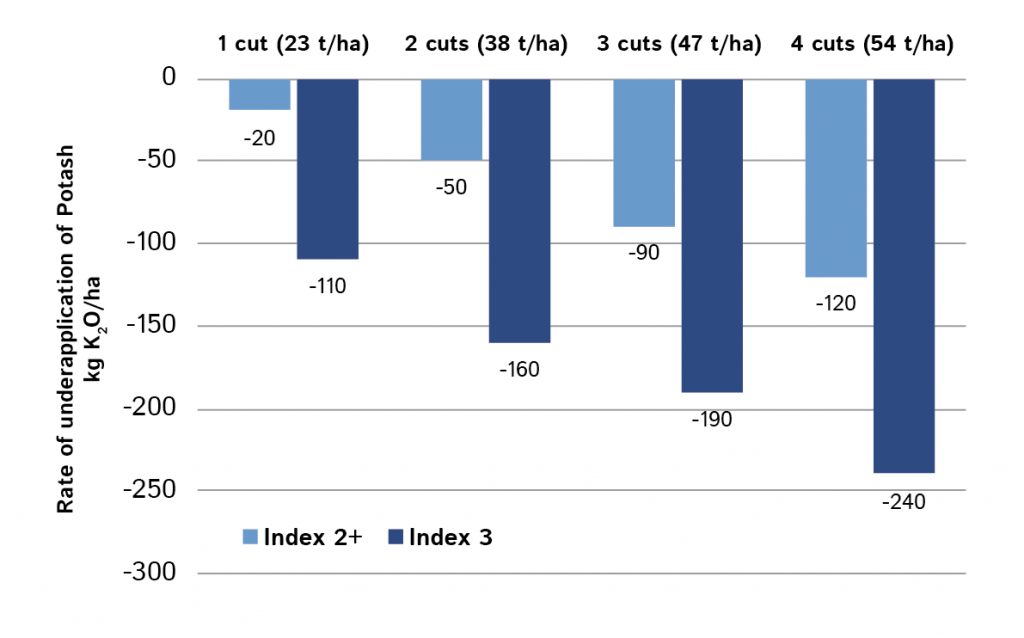

The table opposite, and in the AHDB Fertiliser Manual, implies a fast run-down of potash at index 3 soils under multi-cut management. It recommends 190 kg/ha K2O less than maintenance for 3 cut silage. If fields are in continuous silage production, this is a net removal of 570 kg/ha over 3 years.

Most medium to heavy soils probably have enough buffering capacity to deal with this large deficit, but in such cases it would be prudent to sample soils to the full 15cm depth and retest every 3 years.

The potash requirements in the table are for the middle of each index range and for soils at the lower end of index 3 application rates should be intermediate to those at index 2+.

Potash, magnesium and sodium relationships

Increasing uptake of one nutrient by the plant may affect the level of others, but it is wrong to assume that potash applications automatically lead to mineral disorders. The effect of potash fertiliser on herbage mineral content will vary widely in different situations. The magnesium and sodium % may fall as a result of potash application, however, this is not always the case and may not have any effect on the sodium or magnesium %.

On farms where staggers is a recurring problem, attention should be given to the potassium, magnesium and sodium content of herbage.

Normal magnesium concentrations in herbage are frequently below the minimum 0.20% suggested for animal diets. Magnesium % in plants is affected by a large number of factors and whilst the risk of magnesium disorders may increase with lower herbage magnesium, this is not a reliable measure of whether clinical mineral problems will occur in the animal.

The level of sodium should also be considered. Where herbage sodium levels are above the minimum dietary guide of 0.15% Na, the risk of staggers is low, but rises with lower sodium levels.

Further detail on this can be found in leaflet 6 ‘Potash, Magnesium & Sodium – Fertilisers for Grass’ and the technical note ‘Fertilisers and Hypomagnesaemia: An Historic Exaggeration?’.

Sulphur

Sulphur in the soil acts in a similar way to nitrogen. It is released from the breakdown of organic matter, and to some extent from soil minerals. Soils which are organic, or heavy textured are more able to supply adequate sulphur than light and inorganic soils.

The organic sulphur compounds from applied organic materials and from excreta deposited while grazing, are broken down to inorganic forms, which are then useful to the plant. These sulphate ions reside in the soil solution which means they are liable to be leached, depending on the soil texture and rainfall, just like nitrates. This risk must be taken into account when nutrient planning.

The major role of sulphur in all plants is in support of nitrogen in protein production which is hugely important for high crop yields. However, sulphur is probably more important for improving the quality of grazing and silage, in terms of protein, than the yield increase achieved.

Deficiency symptoms show up in the younger leaves first as a pale-yellow appearance (chlorosis) and, later on, stunting. Symptoms are easily missed, or confused with nitrogen deficiency, and may not be noticed at all, especially in grass.

Leaflet updates

Leaflets 14 ‘Potash for Grass’ and 18 ‘Potash & Sulphur for Grain Legumes’ have both recently been updated on the PDA website.